The Megillat: The Role of Women, Responsibility and the Masquerade of Life

Today we are going to look at writing and imagery around the story of Purim. We will identify some of the key themes, which I hope will relate in some way to experiences in our own daily, cultural and maybe political lives. This isn’t something new to those of you who attend synagogue often. The only difference being is that today, I am arriving at a discussion on the festival from the perspective of other literary and artistic positions. From this I am not necessarily going to suggest that there is a ‘Jewish’ way of looking at art, but instead to consider whether our Jewish lives might offer more multifaceted approaches to interpretations of the visual and literary world outside the synagogue.

This talk comes from my own research into writing and art around the story of Purim. Here I have focused on the two themes that I have found of particular interest in my reading: that being the question of female identity and the blurring of identity through ideas on the hidden and revealed. From this I hope that we will then be able to look at visual depictions around the story of Purim to come up with our own readings on these subjects.

Like rabbis of past generations, we reflect on the stories of our ancestors, making sense of them within the context of our lives. Reading in Judaism involves a process of interpretation. One considers the Hebrew word with reference to the potential of more than one meaning, complicated further by it being found within a sentence constructed without punctuation. The biblical texts in Judaism point inwards and so the ancient language activates the reader in making sense and in creating meaning, to form the layers of metaphor, allegory, and tangible translation.

Susan Handelman quoting Hans-Georg Gadamer explains that Greek philosophy begins with the insight that “a word is only a name” and therefore does not represent a “true being”. Indeed, the Greek term for word onoma is synonymous with name, while the Hebrew term, davar,means not only word but also thing. [1]The indetermination of the term davar does something to explain perhaps the Jewish relationship with language and the importance of study and analysis in Judaism. It also highlights that a word is never fully representative of what it stands in for and so translation is always in flux. In Judaism, a rabbinical reading always returns back to a study of the word, so there is nothing beyond or outside of language. Thinking about this in terms of the visual world around us, we might say that there can be no separating of the visual from the world within which it takes place, and therefore, the visual is always based in language and the world around us.

Consideration of the second of the 10 Commandments can demonstrate this in practice. For some critics a literal interpretation of this commandment “Thou shall have no other gods beside Me. You shall not make for yourself any graven image, nor any manner of likeness, of any thing”, would mean discounting any possibility of the visual arts in Judaism, claiming that it states the position of the Jew as a person concerned with the spirituality of God, rather than the Greek worship of form. It is interesting to note the ways in which Jewish artists worked around the law, which in turn differed according to century and interpretation. While the Talmud takes a strict stance on producing faces for fear of idolatry, bans on creative pursuits differed. So for example, in the 16thcentury, the Shulkhan Arukh[2]extended the ban to creating three-dimensional and bas-relief images that, it was thought, could be worshipped. This differed from the Talmud that allowed two-dimensional images of the human body, as long as some part of the human form remained out of sight.

[3]In order to escape the issue of the prohibition, one has to show that there cannot be an exact translation of an original object or being into an image. In fact the Jewish act of turning away provides an alternative proposition: rather than distrust the image, one places it into language to recognize the potential of different meaning and understanding that can be associated with what we encounter. It may not be a true image, but it is an interpretation, just one of potentially many perspectives.

Unlike the Homeric tradition of writing, and like all biblical stories, not everything is completely externalised within the story of Esther. Thinking further about this in terms of traditional Biblical stories, time and space is often undetermined, and the story fragmentary.The text points inwards to its network of relations, to the “verbal and temporal ambiguities” in written language. This calls for decipherment that does not involve a movement away from the text towards vision or abstraction, but instead we listen or read more intently.[4]Werecognise that the text functions differently depending on the reader, and their immediate, contemporary surroundings. So we might say, even if we are to look at figurative interpretations of the story, these are still perceptions from the artist, based on their understanding. Therefore they offer another route to read the story of Esther and make it significant for us today.

So, the aim today is to look at different readings while reflecting on our collective knowledge and previous experience of the festival, and to think about its significance and appeal today. Looking at representations in art will provide further interpretation and the potential to consider how visual language can affect our speech, writing and the interpretation of other people’s writing to build our own political and social messages. Thus allowing the story of Purim to resonate with us today.

The main theme of the Megillah is the secret, the hidden. Megillah comes from the Hebrew root of revealed and Esther – the main character- from the Hebrew root for hidden. How does this play out with the analogy of reading in Judaism? The characters are never truly as they seem and therefore any representation of these character can activate new interpretations of the role they play within and beyond the story.

I want to begin by focusing on the two main female roles in the story of Purim: that being Esther and Vashti.

At the beginning of the story Esther is little more than decoration: she does whatever her stepfather Mordechai tells her to do and when Queen, she continues to ask for nothing. However, the peak of the story comes when she stands in front of King Ahasuerusand Haman the senior minister, so the story tells us, manipulating them in order to achieve her objective: to save the Jewish people from extermination.

After the edict of Haman in the name of the King, Mordechai and the Jewish people of Shushan are in mourning, trying to determine a way to save themselves from death. Mordechai asks his stepdaughter to go to the King and ask for help. At first Esther refuses, knowing that to go before the King without being summoned may result in the penalty of death. Mordechai then says: “Esther my child, if you keep quiet now and you don’t do anything then salvation will come from a different place, because if it’s G-d’s will to save us then it will happen. You and your family will die however, not in the physical sense, but you will disappear from the World. This is your opportunity to stand and perform the action, the task that you were born to do and if you don’t do it, then your existence was devoid of meaning.” It is worth mentioning that G-d does not appear in the story and so too, is hidden, but he has the will to determine the fate of the Jewish people regardless of any of the characters’ actions. Esther changes her mind and God will act through her. She has found her purpose and will ask for the King’s help.

In the Book of Esther, Vashti is Esther’s predecessor as wife to King Ahasuerus. According to the Midrash, Vashti (ושתי) was the great-granddaughter of King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon and the daughter of King Belshazzar.

As a supposed descendant of the destroyer (Nebuchadnezzar II) of the First Temple in 586 BCE, the sages of Babylon recognized Vashti as being of evil and sinister of character, while the rabbis of Israel lauded her as noble. Vashti’s name is believed to mean “beautiful,” but there have been etymological attempts to understand the word as something more akin to “that drinks.”

According to the Book of Esther, during his third year on the throne, King Ahasuerus decided to host a party. The festivities lasted for half a year and concluded with a weeklong drinking festival. In his drunken stupor, the King decided that he wanted to display his wife’s beauty and so commands Vashti to appear before his male guests. The text does not exactly say how she is to appear, only that she is to wear her royal crown. It is often assumed, given the king’s drunkenness and that all his male guests are likewise intoxicated, that Vashti was commanded to show herself in the nude – wearing only her crown.

Vashti receives the summons while she is hosting a banquet for the women of the court. Refusing to comply one can further assume the nature of the king’s command. After all, why would she risk disobeying a royal decree if King Ahasuerus only asked Vashti to show her face?

When King Ahasuerus is informed of Vashti’s refusal, he is furious. He asks several noblemen at his party how he should punish the queen. One of the eunuchs named Memucan suggests that she should be punished severely. After all, if the king does not deal with her harshly other wives in the kingdom might get ideas and refuse to obey their own husbands. Memucan argues: “Queen Vashti has committed an offense not only against Your Majesty, but also against all the officials and against all the peoples in all the provinces of King Ahasuerus. For the queen’s behaviour will make all wives despise their husbands, as they reflect that King Ahasuerus himself ordered Queen Vashti to be brought before him, but she would not come” (Esther 1:16-18).

Memucan then suggests that Vashti should be banished and the title of queen be given to another woman who is “more worthy” (1:19) of the honour. King Ahasuerus likes this idea, so the punishment is carried out, and soon, a huge kingdom-wide search is launched for a beautiful woman to replace Vashti as queen.

To interpret the main events relating to Esther and Vashti, it might go as the following. For Esther, her true purpose is revealed once she has become Queen, therefore, rather than suggest she is in the position because of her natural beauty and good connections, she was put in that position to leave her mark on history. This was her trial, her destiny. God is hidden and so he is working through Esther to save the Jewish people. She told Mordechai, go and gather the Jews and proclaim a fast for me, and she indeed, stood and performed her diplomatic mission, knowing to perform in the way necessary, to speak properly and appear innocent. From a religious perspective, Mordechai had taught Esther an important idea in Judaism: that everyone has a role in the World, a unique task that no other can do for him or her. In the end, everything that we are – our families, friends, our virtues, defects, our aspirations –are a set of tools provided to us to perform our mission in life. When we live with the awareness that our challenges in life might be part of this mission, writes Rabbi Mijael Even David, to provide us with the experience or maturity to succeed, we will be able to find the strength and wisdom to deal with them and continue forward.

Although Esther and Mordechai are the heroes of the story, others also recognise Vashti as a heroine in her own right. For she refuses to debase herself, choosing to value her dignity above submitting to her husband and his courts men. She does not use her beauty or sexuality to advance herself as some might argue Esther does. And while there have been interpretations that she refuses purely out of a sense of self-importance, or because she wasn’t happy with her appearance that day (some believe she had leprosy), we could also, with our contemporary perspectives consider this as yet another politicised perspective on the female roles in the story of Purim. After all, whether intentional or not, Vashti’s refusal was a humiliation to her husband in front of his guests, but also her a refusal at her own objectification. What we might ask is how Vashti can be considered a hero of the story itself, and in the saving of the Jewish people.

Wendy Amsellem presents a perspective, which I particularly like. She writes that despite the two women never meeting, the relationship between Vashti and Esther is integral to understanding the events of Megillat Esther. At the close of chapter one it is clear that a woman in Ahasuerus’s court would do well to be dutiful and to come before the king as and when he commands. The essentiality of female obedience is confirmed by the final verse of the chapter in which a missive is sent to all the king’s subjects reminding them that, in no uncertain terms, “every man must rule in his household.” At first, Esther is presented as the perfect opposite to Vashti. Rather than independent and headstrong, Esther is passive and submissive. According to Amsellem, the reflexive use of the Hebrew word “LaKaKH” is constantly applied in discussion on her. She is “taken” in by Mordechai as a foster daughter, “taken” to the king’s harem, and “taken” before the king. She does not reveal her identity at the palace, “For Mordechai had commanded her not to tell.” She requests nothing at the harem, only accepting whatever Hagai, the king’s eunuch, chooses to give her. After she is crowned, queen Esther continues to obey the commands of Mordechai. So it is not really any surprise that Ahasuerus loves Esther for she is the model of docility, an exact antidote to Vashti.

Esther understands her role as queen and her refusing Mordechai’s request at first confirms that she has learned from Vashti to come only when she is called. However, at this point in the story Esther is somewhat caught between conflicting obedience to her foster father and husband. Furthermore, going before the king unsummons would be to reject her role as Vashti’s replacement, for she has been chosen to represent the antithesis of her predecessor’s persona. Esther’s position, for her identity and her life are closely tied to her obedience. It is at this point that she looks in the mirror and discovers that she does not appear quite so different from Vashti. She decides then to stand up to both sources of authority. She takes control of Mordechai’s plan, amending it as she sees fit. She will appear before the king only when she decides that the time is right–after three days of fasting. Instead of following Mordechai’s suggestion and simply making her petition, she will host a series of parties as Vashti did. In order to succeed, Esther realizes that she must take on aspects of the former queen.

So while we do not actually know why Vashti refused to appear before the King, her disobedience brings her career to an abrupt end and her fate quite deliberately serves as an object lesson to women everywhere. However, as Esther attempts to gather her strength for the task at hand, she must revisit the experiences of Vashti. More calculated, you might say, or perhaps more subtle and divinely inspired (from a more religious perspective- again still a view on how women should behave), she is ultimately more successful. The perfect post-feminist to Vashti’s proto-feminist, but regardless, Esther must incorporate and discover Vashti’s attributes in her own self to succeed in the task.

So one topic we might want to discuss is Esther asthe archetypal post-feminist. The paintings we’ll look at in a bit will support this discussion. Post-feminism is a movement that is not always clear in it’s ambitions, positioned as anything from reclaiming traditional gender roles, and thus an overt attempt to use the language of oppression to subvert feminism, to a way of depoliticizing feminism in order to bring it into the home. Whichever it is, this is still subject of contention. But this idea of finding one’s purpose, standing up to those who control you – whether they have good or bad intention- and the notion that we all have to find our inner strength, show another ‘side’ of ourselves constantly in life, does not only relate to role of women in society.

The Book of Esther portrays changes in clothing and status throughout. A story full of disguise and masquerade, it places ideas about changing one’s identity and the role of the individual into question. It is written as a comedy of errors involving one masquerade after another, performed over generations until this too became one of the symbols of the festival.

The custom of wearing masks at Purim is documented in 15th-century German sources. Today it is commonly thought that the Italian carnival influenced the custom of dressing up for the festival of Purim, as indicated by illustrated miniatures of the Book of Esther and other Jewish manuscripts. Written evidence of the Purim play only exists from the 14thcentury, but it is thought likely of ancient origin. Jewish performers and musicians did not exist as a professional class until the 18thcentury and so our only source of Jewish popular activities for centuries is the Purim play and wedding entertainment. The content of Purim performances involved socialising, mockery, dressing up as well as a forum for boundary crossing on issues of gender, authority and relations with the non-Jewish world.

A reading of the book reveals that all the characters are perfect foils to their other self. Ahasuerusmasquerades as a tough ruler but turns out to be ruled by his ministers. Haman, who seeks power and respect, is revealed in all his misery, and his disgrace is apparent to all when he is hanged in public. Mordecai sits wearing a sack and ashes outside the palace gate and is presented with royal garments and brought into the palace. Vashti, who is depicted as a successful queen, assertive and experienced is actually revealed as more vulnerable than perhaps she imagines she is, while Haman’s wife turns out, despite his low opinion of her, to be rather wise in comparison to her husband who is revealed as rather ignorant as well as horribly obtuse. Meanwhile The Book of Esther is named after the heroine, who hides her identity until she puts on “the garments of royalty.” With these garments Esther is able to reveal the truth but also drop her obedience and submission. Today Purim is a holiday where Jewish people might explore and challenge certain boundaries through the performances and ritual of dressing as an ‘other’. As Dr. Phina G.Feller suggests, Esther’s story can be re-examined to think about the people we emulate and those we shy away from. We might discover we are not so different from those whom we fear and that the most important lessons might be learned from the unlikeliest of teachers.

Purim invites us to set time aside to remove our uniforms and and reverse our identity: therefore, to cross and reverse in all the other dichotomies and uniforms of our lives. As Feller says: “Purim…makes us wonder if there is an ‘authentic self’ at all, or whether it is all just endless masks upon masks.” We may ask what can lie beneath a festival that is about frivolity and play? To answer: that hidden within the story we can identify aspects that help us move beyond who we are and our present lives, enabling us to become who we aspire to be. (Cohen, D.N.J (2012) Masking and Unmasking Ourselves: Interpreting Biblical Texts on Clothing & Identity).

Finally, the story of Purim teaches us that however much we attempt to control it, life has a way of remaining inescapably unpredictable. While on Yom Kippur we solemnly reflect, Purim is about celebrating the uncertainty, giving our friends and family sweet gifts and giving to the poor. In order to make sense of the randomness of social order, this is a time when we honour the loving relationships that sustain us and work to address the imbalances that leave some with many and other with nothing.

Visual interpretations and the artist’s voice:

At this moment in the story, Esther has revealed the danger she is in, and appealed to the King’s love for her. He looks at the culprit Haman and raises the golden sceptre – that may or may not spell reprieve for his old adviser. Haman himself sits with lowered head, waiting for his fate.

Apart from the dark background, the predominant colour in this painting is gold, closely followed by crimson. With this device, Rembrandt emphasizes the opulence and wealth of Ahasuerus’ court, and the royal status of the couple. The drama played out by the three characters is expressed not by violent action, but by the restraint of their demeanour: the calm before the storm. Esther is radiant, her clothing and headdress gleaming with precious stones. Haman’s persona has already withdrawn into the shadows.

Esther draws away from a terrified Haman as he begs for his life. The implacable anger on Ahasuerus’ face tells the viewer that mercy will not be forthcoming.The figures are positioned so they all converge on the pale figure of Esther – who tries to draw herself away from them. Haman has lost all sense of dignity and thrown himself at her feet, begging for mercy. Her pale right hand is raised in a gesture of refusal. There will be no mercy, and Haman himself will die on the very scaffold he has erected to hang her cousin Mordecai.

Tintoretto is famous for the turbulence and drama of his paintings and in this painting the drama is focused on the fainting Esther, which is mentioned in the Greek edition of the story. She swoons when she sees Ahasuerus’ face full of anger, then, it reads: “God changed the spirit of the king to gentleness, and in alarm he sprang from his throne and took her in his arms until she came to herself.” Tintoretto was one of the first artists to show Esther fainting, an idea that was important because it that linked her to the Virgin collapsing at the foot of the Cross.

Dali was profoundly influenced by Freud’s theory of the Unconscious, and the unconscious dream imagery of Surrealism. His paintings and lithographs appear as dreamlike fantasies. In this lithograph a dream-like Esther is resident in the mind of Ahasuerus, floating there, occupying all his thoughts – and in a sense trapped there.

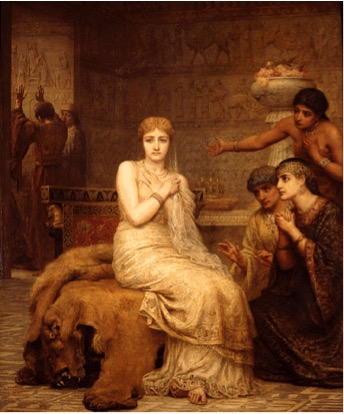

Ernest Normand,Vashti Deposed, 1890

Normand (1857–1923), a notable painter in Victorian Englandpainted history and orientalist paintings. Influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, he painted the nudes in lush settings, and was criticised for an apparent tendency towards an excess of sensuality. Nothing has been written on this artwork that is easily accessible so I thought we might want to analyse it.

The next two paintings are by the same artist, representing Vashti and Esther.

Edwin Long, Vashti Refuses the King’s Summons, 1898

Edwin Long, Queen Esther, 1878

Looking at colour and representation, what strikes you as different in these two paintings? Are the women represented in similar or different ways? What gestures identify these similarities and differences?

So I want to finish by presenting one last painting that represents the story of Purim. Artemisia Gentileschi is possibly the most famous female artist of the seventeenth century and the first female artist to gain a reputation as an accomplished painter of large, multi-figured compositions with a mythological or Biblical theme—the sort of work considered the most demanding test of an artist’s ability. Her pictures very often present violent themes with female protagonists, which are often accredited to aspects of her own biography. Now, I think this is relevant is relatable to the story of Esther and Vashti, for her position as a woman is embedded in her biography as an artist. Instead of focusing on the horrors of her own life, we can reflect on her artworks as narratives relating to human experience and responsibility, regardless of our position in society. For most interesting is her interpretation of the stories of women in the Bible in terms of their position. Using her own visual language, Gentileschi encourages us to enquire into an understanding of familiar narratives beyond what we might assume to know, to re-evaluate the people these stories involve and to create new understanding that renders us all partial.

Gentileschi was trained by her father, Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639), one of the earliest followers of Caravaggio whose Baroque style of painting was characterized by a stark use of light and dark to tell dramatic stories. Most of these paintings were made for the Italian nobility and the church. In 1611, Agostino Tassi, whom her father had engaged to teach her perspective, raped Gentileschi. A trial ensued, in which she was tortured to determine the veracity of her testimony. She was vindicated, and in 1612 was quickly married off to a minor painter (Piermatteo Stiattesi) and moved to Florence. There she established her reputation at the court of Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici and associated with the literary and artistic circle around the poet Michelangelo Buonarroti the younger. In 1616 she became the first female member of the Accademia del Disegno.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Esther Before Ahasuerus,1628-30

In this very large painting, almost seven by nine feet, Esther arrives into the royal throne room, and her courage fails her. She begins to fall into a faint, which arouses the King’s sympathy. Is it merely a ploy on her part? Nowhere in the original Jewish text is there any mention of her swooning before the king. But this incident is depicted in the Midrash and is also retained in the Catholic version.

Artemisia Gentileschi was interested in the effect that light could have in a painting, and here light in the far left corner draws the eye away from the centre: the usual focus for the eye. She heightens this effect by positioning each of the secondary figures around Esther, centring on her as she falls into unconsciousness. The main figures in the painting are represented as sumptuous – not just in clothing and jewellery, but also in personae.

Gentileschi’s imagery closely follows the text of Greek additions made to the original Hebrew narrative, popularly used in the seventeenth century:”On the third day, when she had finished praying, she took off her supplicant’s mourning attire and dressed herself in her full splendour. Radiant as she then appeared, she invoked God who watches over all people and saves them. With her, she took her two ladies-in-waiting. With a delicate air she leaned on one, while the other accompanied her carrying her train. Rosy with the full flush of her beauty, her face radiated joy and love: but her heart shrank with fear. Having passed through door after door, she found herself in the presence of the king. He was sitting on his royal throne, dressed in all his robes of state, glittering with gold and precious stones—a formidable sight. He looked up, afire with majesty and, blazing with anger, saw her. The queen sank to the floor. As she fainted, the colour drained from her face and her head fell against the lady-in-waiting beside her. But God changed the king’s heart, inducing a milder spirit. He sprang from his throne in alarm and took her in his arms until she recovered, comforting her with soothing words. ‘What is the matter Esther?’ he said. ‘I am your brother. Take heart, you are not going to die; our order applies only to ordinary people. Come to me.’ And raising his golden sceptre he laid it on Esther’s neck, embraced her and said, ‘Speak to me.'”

Thinking in terms of an art historical reading of this painting, the handling of light and costumes presents the artist’s renewed acquaintance with Tuscan sources, most probably the work of the Sienese Caravaggesque painter Rutilio Manetti (ca. 1571–1639). Building on this evidence, art historians have examined the picture in light of what we know about Gentileschi’s presence in Venice and her association with a circle of people who formed an informal literary academy, the Accademia de’ Desiosi, as well as the better-documented Accademia degli Incogniti. Among the topics discussed in the latter was the place and nature of women. Unusually, women participated in this discussion, including the Venetian author and poet Lucrezia Marinella (ca. 1571–1653), who wrote a treatise entitled La Nobiltà et l’eccellenza delle donne, co’ diffetti e mancamenti de gli huomini (The nobility and excellence of women, and the defects and vices of men). Consequently, art historian Jesse Locker has suggested that Gentileschi’s painting should be seen as a visual contribution to this debate—painted towards the end of her Venetian sojourn.

In most treatments of the story, writes Keith Christiansen, Ahasuerus is shown sitting regally on an elevated throne, with luscious clothing and holding a sceptre. By contrast, here he is shown foppishly dressed, wearing an extravagantly feathered hat and crown, slashed sleeves, and fur-trimmed, jewelled boots. Locker has noted that the parallels for this kind of dress are to be found on the stage, where it is invariably associated with a comedic character. Thus, by this parodic treatment the artist emphasizes the superiority of Esther and, by extension, of women as rulers.

As Richard McBee points out, of the thirty-four paintings by Gentileschi that survive today, the majority of subjects relate to depictions of women in Christian, or allegorical narratives. However, at least a third of her female subjects were Jewish women heroines, which in the 17thCentury was rather unusual. One could argue, then, that Gentileschi finds her most convincing, strong and vibrant women in the Hebrew Bible and the Midrashim. Susanna and the Elders (a non-Jewish subject from a Hebrew source), Judith Slaying Holofernes, David and Bathsheba, Jael and Sisera and Esther before Ahasuerus.

Back to the painting one can look again at how Gentileschitreats this midrashic swoon in a creative and unusual manner. Esther’s arm is extended out, almost pleading for the king to assist her. Her “artful” collapse is well calculated. While she might seem vulnerable to the king, she is in fact very much in control of the situation. Her head is tilted back at an angle, her eyes closed and eyebrows arched in theatrical abandon. Until we notice that only one knee has given way to throw her off balance we might have thought she would soon end up falling on the floor. She originally swoons out of abject fear of the king’s anger and yet has turned this into a way of causing him to rise in her presence. Gentileschi has thus found a singular place in the story of Esther where a woman can control events usually recognized as beyond her.

Gentileschi painted Jewish female heroines with a certain insight, providing psychological depth and tension to women caught in situations forced to act decisively. So might we recognize Gentileschi’s artistic practice as method for communicating but also protesting against the unfair treatment of women in the 17th century, the brutality of her rape and the trial? Was her source of strength and the substance of her resistance the courage of great Jewish women? But thinking beyond her life, might we think in terms of the paintings as another form of text, asking the viewer to interpret and make it significant for their time? Isn’t the story of Esther about boundaries and the masks we put on to protect ourselves, but also about the way we can change a situation if we just put ourselves in another person’s shoes?

Artemisia Gentileschi’sinsight into Esther and other Jewish heroines shows the richness and depth of the Tanach throughout history. By crossing the boundaries of religious literature and interpretation, the artist created psychologically charged representations of controversial subjects. By doing so she was able to comment on and attempt to shape the world she was living in and provides us today another method by which to recognize the past in terms of our present. Painting, like literature, can have different meanings depending on the person presenting an interpretation and at what point in time this takes place. As we sit here today we have studied together, making these ancient stories resonate in our lives. I believe there is potential from this to link visual and intellectual material with our own political and social positions and experiences, in order to cross the boundaries we create to reveal new meaning where we least expect it.

[1] Susan A. Handelman, Slayers of Moses: The Emergence of Rabbinic Interpretation in Modern Literary Theory(Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983), 3–4.

[2] The legal code known as the Shulkhan Arukh, compiled by the great Sephardic rabbi Joseph Caro in the mid1500s, is still the standard legal code of Judaism. See “Jewish Virtual Library,” http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/shulkhan_arukh.html. [October 8th 2016]

[3] “My Jewish Learning Website,” http://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/ask-the-expert-graven-images/. [Accessed October 8th2016]

[4] Ibid, 31.